#3b──為什麼寫《智者的啟示》?──WHY WAS THE “REVELATION OF THE MAGI” WRITTEN?

為什麼寫《智者的啟示》?

如前所述 ,《智者的啟示》最明顯的特徵之一是它小心避免以「耶穌基督」這個名字來指定智者的天上指南。這種一貫作風在書寫使徒多馬的情節時被打破,在這段書寫中不斷使用這個名字,看上去似乎是如此不和諧。為什麼有作者拒絕使用 「耶穌基督」? 如果在第一人稱敘述的智者的故事中從來沒有使用這個名字 , 意味著他們有經歷基督的經驗在他們甚至不知他就是基督救世主的時候。在這種情況下,智者為我們提供了的這個可能性,基督並沒有把自己透露為耶穌基督給許多人。

實際上,由於智者對天上的基督所作的陳述是確定的,基督的思想在向世人表達的意義上仍然不明,天上的基督告訴智者,他不僅僅只以與他們的宗教一致的方式出現在他們面前。 的確,這只是基督對人類啟示的眾多實例之一,因為他被派去「踐行在全世界和在每一個土地上所說的關於我的一切」(13:10)。 智者聽到了基督的啟示後,便在其他人面前肯定了這一啟示。 他們向耶路撒冷的居民解釋說,他們來信奉基督是「因為他在每個地方都有信徒」(17:5)。 甚至對於孩子的母親馬利亞,他們也堅持基督事件的普遍性和無處不在:「與他同在的形式在每一個土地上都可以看到,因為神派遣他為每個人的拯救和救贖存在」(23:4)

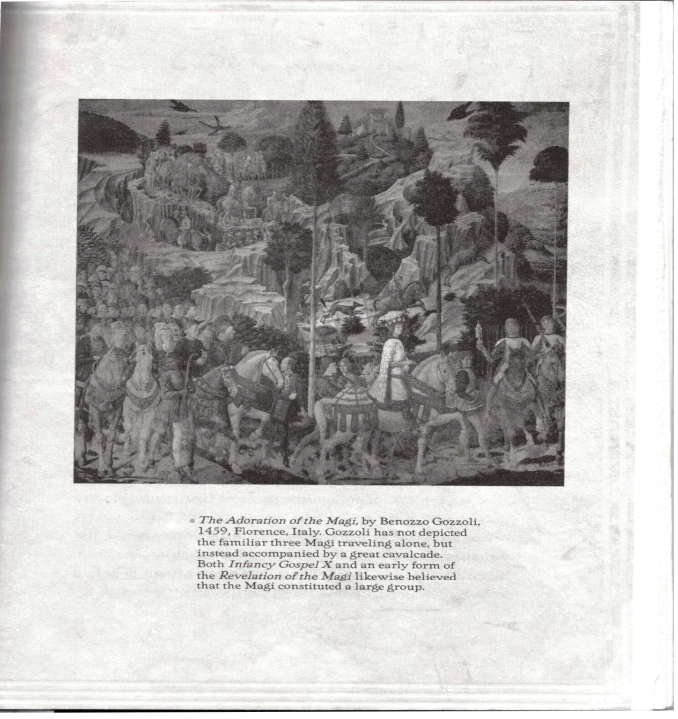

Magnifico 是三位智者中最年輕的一位。壁畫,1459 年。意大利佛羅倫薩美第奇·里卡迪宮。圖片來源:埃里希.萊辛 / 藝術資源,紐約

根據《智者的啟示》,作者講述了關於基督教的基本資訊,就是為了拯救全人類而差遣了基督。 在早期的基督徒中,這是一個足夠普遍的信念,因此它在本文中的存在將是微不足道的。 智者的啟示遠不止於此,它聲稱基督的啟示實際上是全人類宗教信仰和實踐的基礎。智者在實現其古老的預言中所經歷的經歷,儘管對他們而言顯然具有重要意義,但僅僅是「從神秘之屋降下的一滴救恩」(15:1)──基督在全世界救贖活動中的一個有限實例。

一切形式的宗教經驗都是基督的啟示這一信念的實際後果是什麼?我特別想到兩個。 首先,這種信仰意味著《智者的啟示》對非基督教宗教傳統的看法比任何其他早期基督教著作都更為積極。少數早期基督教思想家認為,過去最偉大的異教哲學家曾瞥見過基督──例如蘇格拉底,但這些思想家還堅持認為,與確定的基督真實存在相比,這樣的瞥見是不完整的關於拿撒勒人耶穌基督的啟示。與大多數早期的基督教徒關於非基督教信仰的信仰相比,這種觀點必須記住。絕大多數早期的基督徒,像他們的以色列人的前輩一樣,往往認為別人的神充其量是虛幻的,而惡神則是惡魔。

智者的啟示對基督無所不在的啟示的第二個結果是,它使傳統的基督教擴張模式毫無意義。 在整個基督教歷史上,尤其是自 15 世紀探索時代開始以來,基督教在非基督徒人群中傳播的一種主要手段是通過熱心的傳教士開展工作。人們普遍認為,傳教士的工作是絕對必要的,因為耶穌基督將這項任務委託給了他最忠實的追隨者。

但是,為什麼基督本人不是基督教擴張的主要推動者呢? 如果基督在成為拿撒勒人耶穌之前就存在(如約翰福音的第一節經文所述),甚至可以在耶穌升天後拜訪人們(如使徒行傳聲稱他對使徒保羅所做的事),那麼是什麼原因阻止了基督隨時隨地向任何人顯現呢?這似乎是《智者的啟示》的作者提出的一個問題,他的回答是,「基督在他成為肉身之前並沒有出現在智者面前」,而且,他顯然覺得沒有必要向智者證明自己是基督。可以肯定的是,作者非常擔心基督教的啟示會傳播給世界所有人民,但據他估計,人類傳教士對於這項任務絕不是必不可少的。

如果我們認為基督的觀點是《智者的啟示》作者的核心,那麼,為什麼有人會被迫改變故事的原始結局這一點就變得更加清楚。 隨著《智者的啟示》最初結束,智者和西爾 (Shir) 的人們都開始體驗基督的同在,儘管他們做的是如此完全徹底沒有任何水分,以至於我們可能會把他們與基督教聯繫在一起。 用二十世紀偉大的天主教神學家卡爾.拉納爾的話來說,他們是「匿名基督徒」。 使徒多馬的插曲解決了這個「問題」,智者們接受了使徒的洗禮並受其委託向全世界傳福音。

對於智者的啟示與馬可福音的一個有幫助的模擬是「突然結局」和「更長的結局」之間的差異,表明這很可能是第一本是規範的福音書。 今天,絕大多數學者認為馬可福音的最初結局是在 16:8。 這意味著馬可是以那個女人驚恐地從出現在耶穌空墓裡的天使面前跑開為結束。也就是說,沒有任何復活的耶穌的出現。 因此,馬可會以「他們對任何人都說不出話來,因為他們很害怕」結尾。 儘管「突然結束」的確切理由可能永遠不會完全清楚,但一些學者認為,馬可以此為藉口向聽眾傳達了強有力的神學資訊──儘管脆弱且經常失敗,基督教信仰仍在成長和堅持不斷傳揚基督復活的資訊。

一個強有力的神學資訊,可以說是這福音的光輝結局。但也有一種可能會被誤解或看似不足的情況,特別是考慮到後來的福音書中出現了復活的現象。因此,大概在第二世紀,有人對馬可福音(16:9-20)附加了「更長的結局」,其中包含復活的耶穌的幾種外表,以及耶穌對門徒的教導。換句話說,這個人改變了馬可福音的結局,以更清晰、更明確地反映出當時的基督徒如何期望的福音終結。《智者的啟示》似乎發生了類似的事情。對於智者來說,沒有以直接和明確的方式「使他們成為基督徒」的基督啟示是不夠的,就像馬可福音的婦女們沒有看到耶穌復活的確切證據,僅僅是聽見這樣的資訊是不夠的。因此,馬可福音的結尾和《智者的啟示》的結尾都被改寫和擴展,使它們更符合後來基督徒的典型期望。

因此,《東方博士的啟示》具有其他宗教傳統的觀點,這在早期基督教著作中極為罕見。該功能及其作為關於智者的最長、最深入的次經敘事的地位,應引起基督教起源學者的極大興趣。但是,只有很有限數量的學術專家才能寫出本書所感興趣的《智者的啟示》。在過去的幾年中,我與一些教會團體的成員以及許多親戚朋友分享了我的著作,其中一些人並不認為自己特別虔誠。我相信,他們的熱情回應與智者將自己融入大眾文化的方式有很大關係,其程度超過了聖經中的許多其他人物。越來越少的人會對像使徒保羅這樣具有紀念意義的人有很多瞭解,但似乎每個人都認識智者!

《智者的啟示》確實是一個關於聖經中最有趣的人物的有趣而富有想像力的故事。但是,《智者的啟示》對基督啟示的普遍性的強調也可能使許多讀者著迷。本書提出的問題對於任何認為自己或具宗教精神或僅對神學問題感興趣的人都具有潛在的重要性。基督真的可以成為整個人類歷史上多重啟示的源頭嗎?有什麼辦法知道嗎?這將對基督徒、對非基督徒宗教的態度產生什麼影響?這對傳福音的實踐意味著什麼?如果基督教的啟示僅僅是這種救贖活動的一個孤立的例子,那麼將這樣一個神靈視為「基督」是否正確?有什麼啟示優先於別人嗎?這些問題的答案可能會因人的基本宗教信仰而有所不同。但是,無論是重生的基督徒、後期的聖徒、「宗教尋求者」還是佛教徒,《東方博士的啟示》都提出了關於神的啟示,宗教多元論和宗教多元論的獨特性的挑戰性問題是值得深刻持續反思的問題。

摘自《智者的啟示》

承蒙神召會活水堂授權【葡萄樹傳媒】轉載

WHY WAS THE “REVELATION OF THE MAGI” WRITTEN?

──Brent Landau

As mentioned earlier, one of the most noticeable features of the Revelation of the Magi is its careful avoidance of the name “Jesus Christ” to designate the Magi’s celestial guide. This consistent omission is one of the reasons that the Apostle Thomas episode’s free use of the name seems so jarring. Why has the author refused to use the name “Jesus Christ?” If the Magi in the first-person narrative come to the end of the story without ever using the name, this implies that they have had an experience of Christ without ever knowing this savior figure as Christ. The case of the Magi, then, raises the possibility that Christ has appeared to many people and yet not revealed himself as Jesus Christ.

The idea of Christ remaining unidentified in manifestations to the peoples of the word is, in fact, affirmed by statements that he celestial Christ makes to the Magi. He tells them that he has appeared not only to them in a manner congruent with their religion. Indeed, this is only one of many instances of Christ’s revelation to humanity, since he has been sent “to fulfill everything that was spoken about me in the entire world and in every land” (13:10). Having heard this revelation from Christ, the Magi themselves then affirm it before others. To the inhabitants of Jerusalem, they explain that they have come to worship Christ“ because he has worshipers in every land” (17:5). Even to the child’s mother, Mary, they insist on the universality and omnipresence of the Christ event: “[T]he forms with him are seen in every land, because he has been sent by his majesty for the salvation and redemption of every human being” (23:4).

According to the author of the Revelation of the Magi, the fundamental Christian message is not simply that Christ has been sent in order to save all humanity. That is a common enough belief among early Christians that its presence in this text would be unremarkable. The Revelation of the Magi goes much further than this, claiming that the revelation of Christ is actually the foundation of all humanity’s religious beliefs and practices. What the Magi have experienced in the fulfillment of their age-old prophecy, while obviously of great significance for them, is but “one drop of salvation from the house of majesty” (15:1) – one limited instance of Christ’s salvific activity in the world.

What are the practical consequences of this belief that all forms of religious experience are revelations of Christ? Two especially come to mind. First, this belief means that the Revelation of the Magi has a far more positive view of non-Christian religious traditions than any another early Christian writing. There were a handful of early Christian thinkers who held that glimpses of Christ were had in the past by the greatest of the pagan philosophers – Socrates, to name one example. But these thinkers also maintained that such glimpses were woefully incomplete when compared with the definitive revelation of Christ in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. And such an opinion, it must be remembered, is quite charitable when compared with most early Christian beliefs about non-Christian religions. The vast majority of early Christians, like their Israelite forebears, tended to regard the gods of other people as illusory at best, demonic at worst.

A second consequence of the Revelation of the Magi’s opinion about Christ’s all-encompassing revelation is that it renders the traditional model of Christian expansion completely pointless. Throughout much of Christian history, and particularly since the beginning of the Age of Exploration in the fifteenth century, one dominant means by which Christianity has spread among non-Christian populations is through the work of dedicated missionaries. The general assumption is that the work of missionaries has been absolutely necessary because Jesus Christ delegated this task to the most devoted of his followers.

But why would not Christ himself have been the principal agent of Christian expansion? If Christ existed before Jesus Nazareth did (as the first verses of the Gospel of John claim) and could even visit people after his ascension (as Acts of the Apostles claims that he did to the Apostle Paul), then what would prevent Christ from appeared to anyone, in any place, at any time? This appears to have been a question asked by the author of the Revelation of the Magi, and his answer was, “Nothing” Christ appeared to the Magi before he assumed human flesh, and what is more, he apparently felt no need to identify himself to the Magi as Christ. The author, to be sure, is very concerned that the Christian revelation be spread to all the people of the world, but in his estimation, human missionaries are in no way essential for this task.

If we see this view of Christ as central to the author of the Revelation of the Magi, then it becomes much clearer why someone else would have felt compelled to change the original ending of the story. As the Revelation of the Magi originally ended, the Magi and the people of Shir has all come to experience the presence of Christ, though they have done so completely without any of the trappings that we might associate with institutional Christianity. They are, in the words of the great twentieth century Catholic theologian Karl Rahner, “anonymous Christians. ”The Apostle Thomas episode solves this “problem” by having the Magi baptized and commissioned by an apostolic emissary to go preach the Gospel throughout the entire world.

A helpful analogy for what has happened to the Revelation of the magi would be the difference between the “abrupt ending” and the “longer ending” of the Gospel of Mark, most likely the first of the canonical Gospels to be written. The vast majority of scholars today believe that the original ending of Mark’s Gospel was at 16:8. This would mean that Mark ended with the woman running terrified from the angel’s appearance at the empty tomb of Jesus – that is, without any appearances of the resurrected Jesus. Mark would therefore have ended with the words “they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.” Although the precis reasons for the “abrupt ending” will likely never be completely clear, some scholars believe that by it Mark intended to convey a powerful theological message to his audience – possibly that Christian faith grows and perseveres in spite of the frailty and often failure of its would-be messengers.

A powerful theological message, and arguably a brilliance ending to this Gospel. But also one that could be misunderstood or seem rather inadequate, particularly given the presence of Resurrection appearances in later Gospels. So someone, probably in the second century, attached a “longer ending” to Mark’s Gospel (16:9-20) that contained several appearances of the risen Jesus, along with Jesus’s missionary charge to his disciples. In other words, this individual changed the ending of Mark’s Gospel to reflect much more clearly and explicitly how Christians in his time and place expected a Gospel to end. Something much like that seems to have happened to the Revelation of the Magi. It was simply not good enough for the Magi to have had a revelation of Christ that did not “make them Christians” in a straightforward and unambiguous way, just as it was not good enough for the women of Mark’s Gospel to hear that Jesus had been raised without seeing any definitive evidence of it or telling anyone about what they saw at the bomb. Hence, the endings of both Mark’s Gospel and the Revelation of the Magi were rewritten and expanded to make them more palatable to the typical expectations of later Christians.

So, the Revelation of the Magi has a view of other religious traditions that is highly unusual among early Christian writings. That feature, along with its status as the longest and most developed apocryphal narrative about the Magi, should make it considerable interest for scholars of Christian origins. But the present book would not have been written were Revelation of the Magi of interest for only a limited number of academic specialists. Over the past several years I have shared my work on this writing, with members of several church communities and with a number of friends and relatives, some of whom do not consider themselves especially religious. Their enthusiastic response, I believe, has much to do with the way in which the Magi embedded themselves in popular culture to a degree surpassing many other figures from the Bible. Fewer and fewer people may have much understanding of such a monumental personality as, say, the Apostle Paul, but it seems as if everyone knows the wise men!

The Revelation of the Magi is indeed a fascinating and imaginative story about some of the Bible’s most intriguing figures. But the emphasis of the Revelation of the Magi on the universality of Christ’s revelation may also captivate many readers. The questions this writing poses are of potential importance for anyone who consider herself or himself religious, spiritual, or simply interested in theological questions. Could Christ actually be the source of multiple revelations throughout human history? Would there be any way of knowing this? What would the implications of this be for Christian attitudes toward non-Christian religions? What would this mean for the practice of evangelism? Would it even be correct to regard such a divine being as “Christ” if the Christian revelation is but a single isolated example of this being’s salvific activity? Does any revelation take precedence over others? The answers to these questions will probably differ depending on one’s basic religious convictions. But whether one is a born-again Christian, a Latter-day Saint, a “religious seeker,” or a Buddhist, the Revelation of the Magi raises challenging questions about divine revelation, religious pluralism, and the uniqueness of religious pluralism, and the uniqueness of religions – questions that merit deep, sustained reflection.

支 持 我 們

靈修小品:

# TAG

EN English MONDAY MANNA 中國成語 以色列 以色列新聞 你累了嗎 保捷 信仰見證 出埃及記 利未記 創世記 劉國偉 原文解經 國度禾場KHM 天人之聲 天堂 奇妙的創造 妥拉 妥拉人生 家庭 市井心靈 張哈拿牧師 愛情 敬拜 智慧 梁永善牧師 歳首到年終 民數記 清晨妥拉 漫畫事件簿 為以色列代禱 琴與爐 申命記 真理 知識 研經課程 箴言 考門夫人 聖經 荒漠甘泉 見證 週一嗎哪 靈修 靈修文章